The Logic of Dynamic Tension

by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti

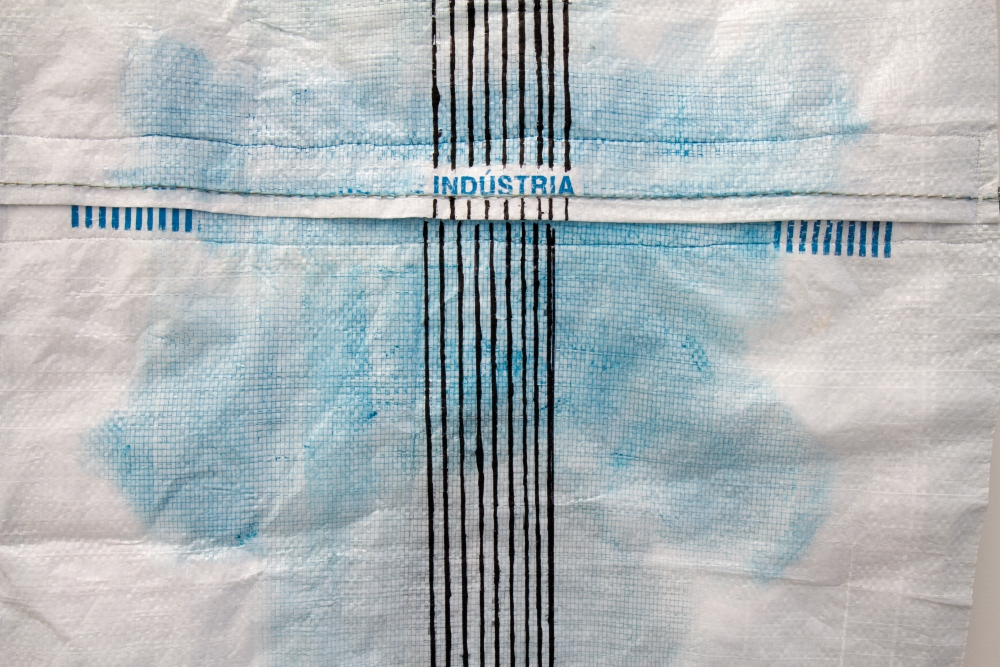

Since at least Oeste, ou até onde o sol pode alcançar [West, or to Where the Sun Can Reach] (2006) – an action recorded in video in which André Komatsu tried to walk through the city, with the aid of a compass, always heading in the same direction (toward the west), and naturally coming up against countless obstacles – the attempt to cross over walls and barriers is recurrent in his work. It generally seems valid to say that his works remain in a constant state of tension, on the one hand striving for a condition of equilibrium, while simultaneously denying that same balance, which is undermined either by the artist’s own effort, or by that of the world, aimed at toppling, breaking, disarranging or exploding apparently solid structures. The situation of struggle – at times explicit and evidently political, at others more metaphoric and allusive than real, and at still others related only to the clashing of the materials used – is the feature that most clearly defines the artist’s poetics. In the specific context of colliding with barriers of the city (or of the exhibition space), for example, Komatsu has used (or, more or less directly, invited the public to use) sledgehammers, hammers, punches, kicks, head butts, fire, urine, saws, a hydraulic jack… If this state of dynamic tension is explicit in the performances and actions carried out by the artist since the beginning of his career, it also pervades his more sculptural works, hence the adoption of the idea of tension as the fundamental feature in the conception of this book. Consequently, the works have not been organized chronologically, seeking to shed light on a theoretical evolution in Komatsu’s work, but rather based on conceptual analogies, with the aim of precisely evidencing the work’s dynamic state.

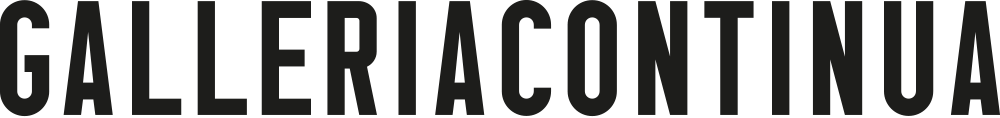

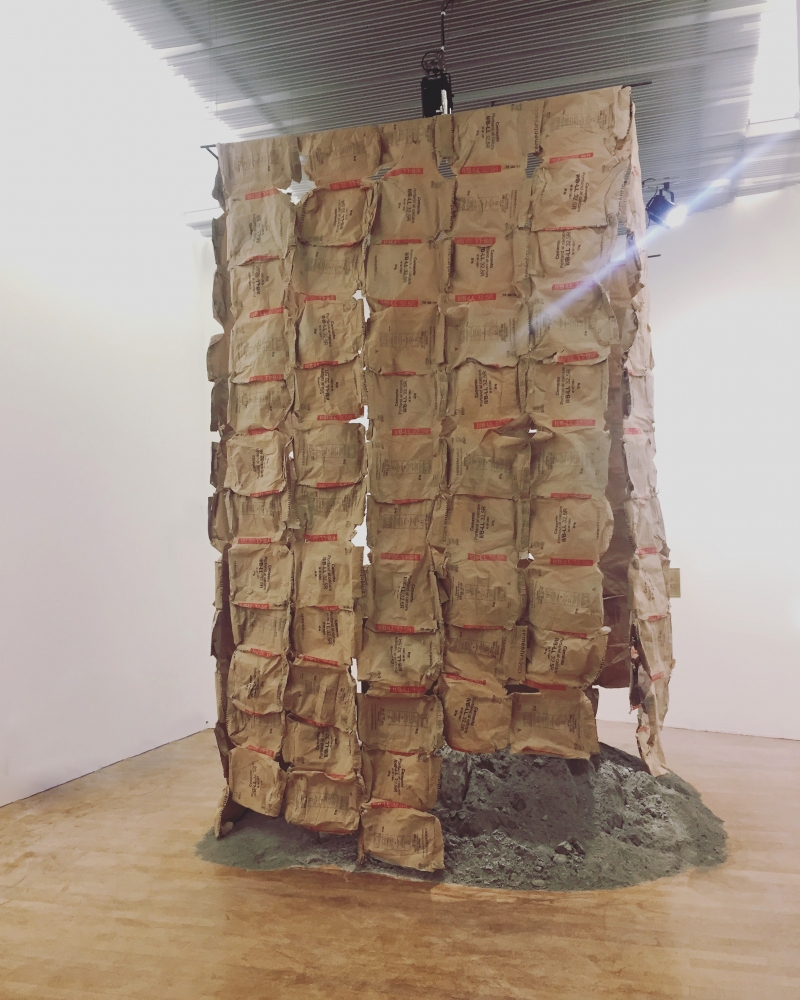

The movement (real, potential or merely implied) that characterizes various of his works, coupled with the choice of common materials, for the most part used in civil construction, allows for an engaged and ideological reading of his work, even in cases where formal issues seem to be central. Titles such as Suspensão estrutural de poder [Structural Suspension of Power] (2012), Cooperativa antagônica [Antagonistic Co-Operative (2013) or Desvio de poder [Diversion of Power] (2011) suggest Foucaultian recollections, reinforcing the feeling that, beyond the titles, Michel Foucault’s microphysics of power lies at the core of the artist’s concerns and even, if you will, his worldview. The discourse about power and more or less latent social conflicts pervades the materials, influences their choice, and in a certain way constitutes the true raw material of Komatsu’s sculptures and installations. In this sense, the discarded fragments, scraps and leftovers found in dumpsters, which have been recurrently present since the action-performance Projeto – Casa/entulho [Project – House/Rubble] (2002), also reveal the wish to subvert the values conventionally attributed to the materials themselves and, generally, to the elements of everyday life, installing a “new order,” to cite the title of another work, Nova ordem [New Order] (2009).

In another work, Base hierárquica [Hierarchical Basis] (2011–) – produced in different versions in various countries where Komatsu has shown it, each time resorting to common drinking glasses, wineglasses and construction materials widely found in the local markets – concrete blocks or bricks are supported atop drinking glasses and coffee cups of a cheap sort and yet strong enough to (together) support the weight, while the splinters of the wine glass attest to the fragility of its elegance. This work exemplifies the simplicity with which the artist transforms “classic” sculptural questions (the weight, strength and mass of some materials or objects) into signs of a conflict between sociopolitical models (stated more simply: the proletariat united in the construction of the world, against the egoistic fragility of the elites, doomed to disaster). As in Base hierárquica, in several of his works Komatsu analyzes the construction of his own structures, but they rarely have a solid and stable appearance. More often, as in, for example, XYZ e aglomerado subnormal [XYZ and Subnormal Agglomerate] (2011), the state of balance is evidently precarious to the point of having a miraculous aspect. Commodities like salt, sugar and coffee, whose economic value is subject to constant negotiation, are often used in his work precisely for serving as signs of an imminent disequilibrium, a foretold fall. Once again, the observer finds himself in a dynamic, volatile situation. In this sense, perhaps, it is necessary to understand the recurring presence of wreckage as an affirmation of equivalence between construction and destruction, considered by the artist as different moments of single and unceasing process of transformation. A process that also takes place with the artist’s own body, which in Disseminação concreta [Concrete Dissemination] (2006) seems to be made entirely of rubbish.

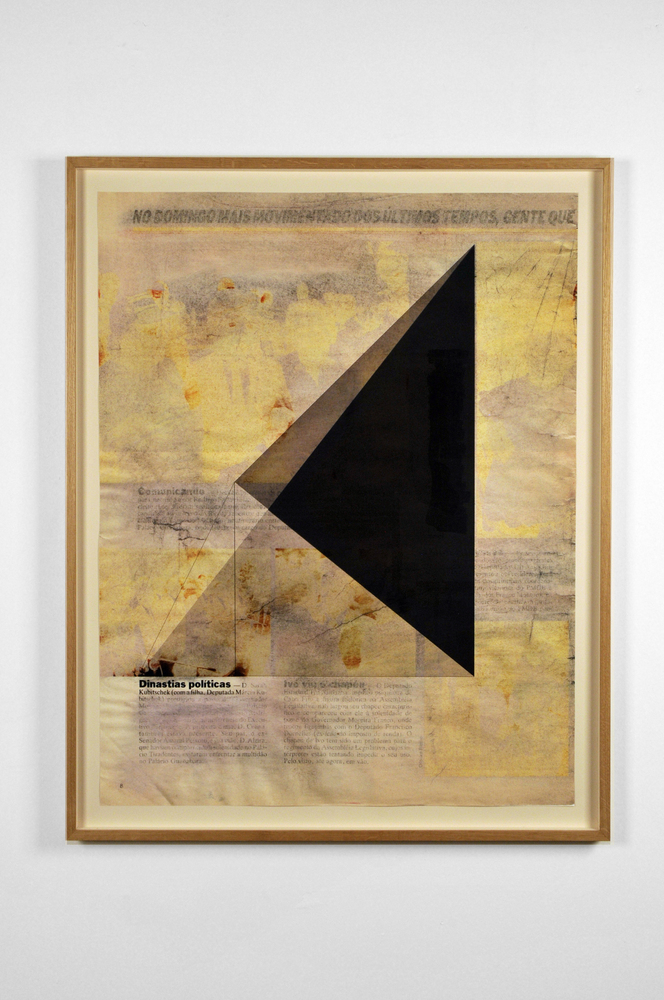

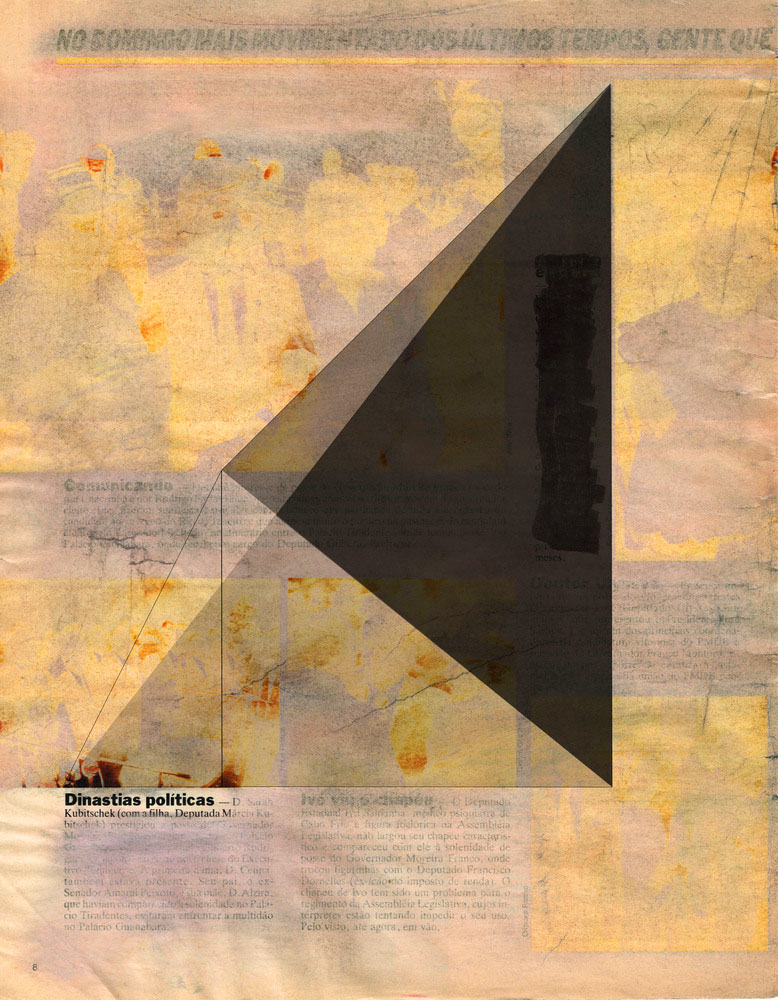

In the works of the series Três vidros [Three Panes of Glass] (2012), the fragments become the raw material for the construction of architectures with modern lines, isolated on perfectly flat lots, in total conformity with modernist precepts. When icons of the golden era of Brazilian architecture are transformed into agglomerations of scraps, this can be interpreted as the denouncing of the violence implicit to the constructive process, or of the unique qualities that this architecture – whose democratic dreams were shipwrecked on the shoals of its progressive approximation with the social, political and economic elites – winds up validating and preserving by its clean and simple lines. The tension between elements which are, on the one hand, natural, fragmented and apparently disarranged, and on the other, precise and rigorous, is recurrent in Komatsu’s work, but this contrast is in a certain way illusory, as is demonstrated by the twisted and raw branch, which nevertheless fits perfectly as a leg for a precisely square tabletop (Cooperativa antagônica, 2013), or even the image of a tree trunk printed on an anonymous, simple sheet of paper, which nearly seems to be part of the wooden beam that secures it against the wall, at its top (Campo aberto 4 [Open Field 4], 2013). Because of these polarities (natural and artificial / geometric and organic / raw and finished, etc.), the artworks constitute open fields, as though they were yet about to take place in front of the viewer, rather than being presented in an already finished state.

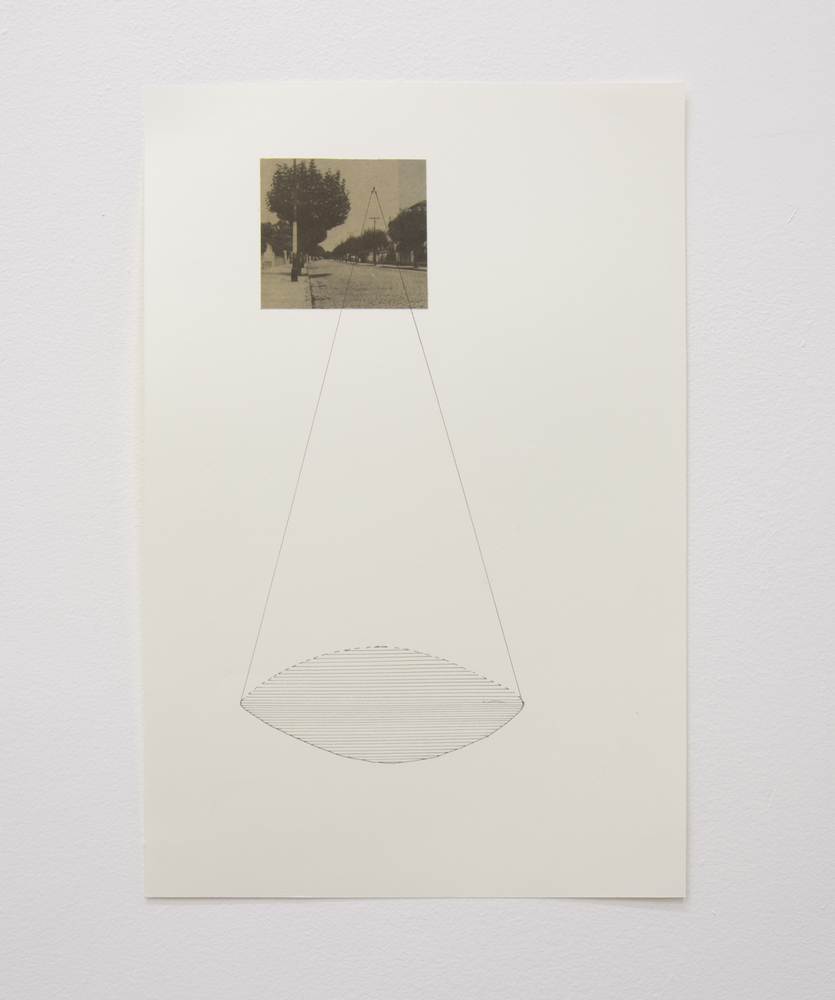

By directly or indirectly resorting to the technique of anamorphosis (Anamorfose sistemática 3 e 4 [Systematic Anamorphosis 3 and 4], both from 2012, and Campo aberto 2, 2013), the artist further emphasizes the need for an interpretation which is political or in any case metaphoric. The key for the comprehension of an anamorphosis is almost always a change of vantage point, a displacement that permits us to look at things from another point of view, allowing us to see that what appeared obscure and abstract is in fact perfectly logical and understandable. And this is precisely what most of Komatsu’s works require: a change in one’s point of view, as they are open to various readings and to being understood in different ways. The bricks, the architectures and the clocks that converge on his artistic universe are, beyond what they appear to be, invitations to social resistance. A work such as Time Out (2013), for example, in which a stack of bond paper prevents the hands of a clock from following their course, is above all a social and political manifesto. The metaphorically charged act of stopping time would be impossible for a single sheet of paper, and the power of this artwork, beyond its poetic beauty, consists precisely in demonstrating the revolutionary power that springs from the union of individual forces, able to achieve otherwise impossible gestures.

This same charge appears in a work that escapes from the prevailing logic of tension, but for this very reason provides an important key for its understanding: Esquadria disciplinar / Ordem marginal [Disciplinary Frame/Marginal Order] (2013). Apparently, the contraposition between different orders is absent here: the two groups of steel sheets, the second one resulting from the “leftovers” of the first, both obey the same rigorous and deductive logic. But some sheets are still left over, and return, like a kind of virus, infringing on the bidimensionality that seems to dominate the work, jutting out from the wall and proposing, in the words of the artist, “another model of coexistence.” In André Komatsu’s open universe, the very concept of order is, one could say, marginal, rather than central. Order, as it is conventionally known, is just one of the possible ways in which the world can be manifested – and it is not necessarily the most easily understood one. It is enough to take a step, to look at things from another angle, and what at first sight appeared ordered can be revealed as disordered, what looked chaotic can, ultimately, be seen in its flawless logic.